1.0 Introduction

Cancer is the leading cause of death worldwide, with an estimated 19.3 million new cases and about 10.0 million deaths reported globally in 2020 (Sung et al., 2021). In 2020, the top five leading causes of cancer-related death were lung, liver, stomach, breast, and colon cancers. Lung cancer remained the primary cause of cancer-related deaths, with an estimated 1.8 million fatalities (18%). Following lung cancer were colorectal (9.4%), liver (8.3%), stomach (7.7%), and female breast (6.9%) cancers (Cao et al., 2021; Sung et al., 2021). In Sub-Saharan Africa, there is a pressing demand for prompt actions to tackle the increasing challenge of soaring cancer rates and fatalities. Delaying action could result in a notable increase in deaths related to cancer, with forecasts suggesting a rise from 520,348 in 2020 to around 1 million deaths per year by 2030 (Gourd & Collingridge, 2022; Ngwa et al., 2022).

Nigeria, with a population of about 200 million people, witnesses an estimated 72,000 cancer-related deaths each year (Fatiregun et al., 2020). Despite the progress made in cancer treatment, the outlook for cancer patients continues to be discouraging as tumors frequently become resistant to existing drugs, reducing their effectiveness and leading to increased tumor aggressiveness and poorer patient outcomes. Therefore, there is a need for a novel alternative therapeutic strategy. The enduring legacy of plant-based knowledge, particularly within African traditional medicine, continues to provide an invaluable roadmap for modern anticancer drug discovery. This is powerfully evidenced by the fact that natural products form the foundation for a significant majority of FDA-approved chemotherapeutic agents, with landmark drugs like vincristine and paclitaxel originating directly from botanical sources (Asma et al., 2022)

Despite these successes, the profound limitations of conventional therapies, including severe side effects and the inevitable emergence of drug resistance, underscore a persistent and urgent need for safer, more effective alternatives (Birat et al., 2022; Gallego-Jara et al., 2020). This ongoing challenge reaffirms that the systematic investigation of medicinal plants, guided by indigenous knowledge, remains an indispensable and promising strategy for uncovering novel bioactive compounds with targeted antitumor potential (Sahu et al., 2023; Orobator et al., 2025).

Khaya senegalensis (Desr.) A. Juss., a towering deciduous tree native to sub-Saharan Africa, is esteemed not only for its high-quality timber but also for its profound ethnomedicinal significance (Arnold & Arnold, 2004; Sahu et al., 2023).

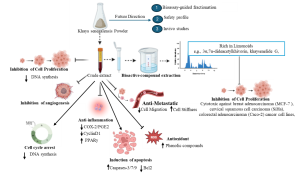

For generations, traditional healers have employed preparations from its bark, leaves, and seeds to treat a wide spectrum of ailments, including malaria, diabetes, and inflammatory diseases, with a notable history of use against abnormal growths and tumors (Ataba et al., 2020; Inngjerdingen et al., 2004; Ka et al., 2018; Tchacondo et al., 2012; (Azeez et al., 2025; Agwupuye et al., 2025). This traditional application is supported by a rich phytochemical profile, particularly its prolific production of limonoids, a class of highly oxidized tetranortriterpenoids known for their diverse bioactivity(H. Zhang et al., 2007a; W.-Y. Zhang et al., 2018). The documented anticancer properties of limonoids from related Meliaceae species, coupled with the initial identification of bioactive compounds like the senegalenines in K. senegalensis, provide a compelling rationale for its systematic investigation. Therefore, this review aims to synthesize the current evidence on K. senegalensis, critically evaluating its phytochemistry, elucidating its mechanistic actions against cancer pathways, and assessing its potential as a source of novel anticancer agents to bridge the gap between traditional wisdom and modern therapeutic discovery.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of anticancer potentials of Khaya Senegalensis

2.0 Botany of the Khaya Genus

The mahogany family, Meliaceae, is a pantropical group of 51 genera and roughly 1,400 species, many of which are large trees renowned for their valuable timber. Among the most commercially significant genera are Swietenia (Central and South American mahogany), Cedrela, and Entandrophragma, alongside the African genus Khaya (Olatunji et al., 2021). Within Africa, Khaya, commonly known as African mahogany, is the preeminent commercial timber genus in the Meliaceae family. It comprises five primary species: K. anthotheca, K. grandifoliola, K. ivorensis, K. nyasica, and K. senegalensis (Olatunji et al., 2021; Tchacondo et al., 2012). These species are distributed across the continent and have been cultivated in tropical regions worldwide. True to their families’ reputation, all Khaya species produce high-quality hardwood. Their timber is not only prized for its workability and appearance but also for its natural durability, demonstrating notable resistance to insect and fungal attack (Olatunji et al., 2021; Tchacondo et al., 2012).

Botanically, the genus Khaya is closely allied with Swietenia, the source of commercial mahogany from the Americas. This phylogenetic relationship is reflected in their similar wood properties and structure, which allowed African mahogany to become a leading substitute for its New World cousin as those stocks became depleted (Olatunji et al., 2021).

2.1 Botany and Distribution of Khaya senegalensis

Among its congeners, Khaya senegalensis is a particularly distinct species, often distinguished in the timber trade as heavy African mahogany. This common name refers to its characteristically dark color and high density; with an average dried weight of 800 kg/m³, it is markedly heavier than other commercially important Khaya species such as K. ivorensis (530 kg/m³) or K. anthotheca (540 kg/m³) (Langa et al., 2024). Botanically, K. senegalensis is a large evergreen tree, typically reaching heights of 15 to 24 meters with a substantial trunk diameter of up to 3 meters. It is easily recognized by its dense, dark green crown of glossy, pinnate leaves and its distinctive spherical seed capsules (Langa et al., 2024).

The species is naturally distributed across the deciduous savannah woodlands of West and Central Africa. Its range is primarily concentrated within a belt stretching from Senegal through Nigeria and into Sudan and Uganda (Langa et al., 2024). This ecology is key to its identity, setting it apart from other mahoganies that favor wetter rainforest habitats. The combination of its density and durability makes its timber highly prized. It is considered to offer one of the finest surface finishes of all the African mahoganies, leading to its use in high-quality furniture, cabinetry, and interior joinery. Beyond these traditional applications, its strength also lends itself to heavy-duty uses such as lorry (truck) bodies, structural construction, and marine decking (Arnold, 2004; Langa et al., 2024). Despite its resilience, overexploitation for its high-quality timber has led to significant population declines, earning it a Vulnerable status on the IUCN Red List (IUCN, 2019).

2.2 Traditional Uses of Khaya senegalensis

Khaya senegalensis (Desr.) A. Juss., widely known as African mahogany, is much more than a timber tree. Across its native range in sub-Saharan Africa, it is deeply ingrained in the cultural and socio-economic fabric of local communities, especially in rural areas, where it serves as a vital resource for health, livelihood, and material needs. For generations, the stem bark of K. senegalensis has been a cornerstone of traditional medicine systems. It is commonly employed as a tonic to combat malaria and fever, to address gastrointestinal issues like mucous diarrhea, and to manage venereal diseases. Its potent anthelmintic properties also make it a trusted remedy for parasitic worms (Abdelgaleil et al., 2004; Ataba et al., 2020; Elisha et al., 2013; Langa et al., 2024) (Table 1).

In Northern Nigeria, for example, traditional practitioners in Sokoto report using powdered or decocted bark, administered both orally and topically, in the treatment of cancer (Malami et al., 2020) (Table 1). Beyond its bark, communities utilize nearly every part of the tree. The leaves, roots, and seeds are also harnessed for various medicinal preparations, often applied topically for skin conditions or inhaled for respiratory ailments like coughs and bronchitis (Langa et al., 2024). This extensive use reflects a profound, generational knowledge of the plant’s therapeutic properties. The value of K. senegalensis extends well beyond the clinic. Its wood is highly prized for its durability, rich color, and natural resistance to pests, making it a preferred material for crafting furniture, canoes, and tools, and for use in construction (Langa et al., 2024). This has cemented its role as an important economic engine for local economies. However, this multi-purpose utility is a double-edged sword. The combination of high medicinal demand and intensive timber exploitation has led to severe overharvesting. When coupled with ongoing habitat fragmentation and climate change, these pressures have pushed natural populations of K. senegalensis into decline.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed K. senegalensis as vulnerable, a status that underscores the urgent need to develop strategies that balance its traditional and commercial use with serious conservation efforts (IUCN, 2019). Importantly, the traditional claims surrounding K. senegalensis have not gone unnoticed by modern science. A growing body of phytochemical and historical uses. Extracts from the stem bark have demonstrated a remarkable range of bioactivities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial (Rabadeaux et al., 2017), antidiarrheal (Elisha et al., 2013), antifungal (Abdelgaleil et al., 2004), and anti-plasmodial effects (Androulakis et al., 2006).

Critically, several studies have also confirmed its antitumor and chemopreventive properties (Androulakis et al., 2006; Rabadeaux et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2007b), providing a scientific foundation for its use in cancer treatment and positioning it as a promising candidate for the development of novel therapeutic agents.

Table 1: Summary of the Traditional Ethnomedicinal Uses of Khaya senegalensis

| Part(s)Used | Mode of / Preparation | Route of Administration | Disease Condition (Indications) | References |

| Leaves | Decoction | Oral | Malaria; Fainting | (Tchacondo et al., 2012) |

| Roots | Decoction | Oral | Malaria, Sickle Cell Disease, Stomachache, Hypertension, Fainting | (Tchacondo et al., 2012) |

| Roots | Decoction, Powder | Anal (enema) | Hemorrhoids | (Ka et al., 2018; Tchacondo et al., 2012) |

| Stem Bark | Decoction | Oral | Infectious Diseases; Epilepsy; Female Infertility; Diabetes; Boils; Mental & Neurological Disorders | (Inngjerdingen et al., 2004; Ka et al., 2018; Magassouba et al., 2007; Tchacondo et al., 2012) |

| Bark (inner & external) | Powder | Topical | Insect/Snake Bites; Wound Healing | (Inngjerdingen et al., 2004) |

| Stem Bark, Root, Leaves | Dough, Decoction | Topical, Oral | Lymphatic Filariasis, Onchocerciasis | (Ataba et al., 2020) |

| Stem Bark | Decoction, powder | Oral, Topical | Cancer | (Malami et al., 2020) |

2.3 Phytochemistry

Khaya senegalensis is a veritable storehouse of diverse and biologically significant phytochemicals, with its therapeutic potential underpinned by a complex array of compounds. Investigations across various plant parts, including the bark, leaves, roots, and twigs, have consistently revealed the presence of fundamental classes such as tannins, flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, terpenoids, phenols, and steroids (Kubmarawa et al., 2008; Marius et al., 2020; Rabadeaux et al., 2017). Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) studies of the stem bark highlight a rich profile of fatty acids, including n-hexadecanoic (palmitic), oleic, stearic, and 9,12-octadecadienoic (linoleic) acids, alongside various alcohols and other organic compounds (Aguoru et al., 2017).

This fatty acid composition, characterized primarily by monounsaturated structures, is notably well-suited for biodiesel production (Okieimen & Eromosele, 1999; Omotoyinbo et al., 2019). The plant is particularly renowned for its limonoids, a class of highly oxidized tetranortriterpenoids. From the leaves and twigs, researchers have isolated eight new limonoids, named khayseneganins A−H, in addition to 31 known analogues, their structures meticulously elucidated through 2D-NMR and mass spectrometry (Yuan et al., 2012). The bark is also a source of unique triterpenoids of the mexicanolide type, such as 2-hydroxymexicanolide, which have been linked to its traditional use for treating skin ailments, diarrhea, and rheumatic pains (Kankia & Zainab, 2014). Furthermore, extraction techniques like sub-critical fluid extraction (SFE) have unveiled a suite of sesquiterpenoids in the bark, including spathulenol, globulol, and γ-eudesmol (Rabadeaux et al., 2017).

The roots contribute their own unique chemistry, yielding various chromone derivatives like 5,7-dihydroxychromone (Ibrahim et al., 2014). Beyond these secondary metabolites, K. senegalensis is a source of essential minerals, including calcium, magnesium, potassium, iron, and zinc (Idu et al., 2014), and contains other chemical groups such as carotenoids and coumarins (Takin et al., 2013). This extensive phytochemical diversity is a strong foundation for the plant’s wide-ranging ethnomedicinal application.

3.0 Anticancer properties of Khaya senegalensis

3.1 Anti-Proliferative Effects

Research by Androulakis et al. (2006) provided foundational evidence for the anti-proliferative properties of Khaya senegalensis (Fig. 1). Their work showed that its bark extract significantly suppresses the viability of HCA-7, HT-29, and HCT-15 colorectal carcinoma cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner. The extract’s potency, quantified by IC₅₀ values, was highest against the HCA-7 cell line (0.22 μg/μl). Complementing these findings, a ³H-thymidine incorporation assay demonstrated that Khaya senegalensis bark extract’s growth-inhibitory effects are mediated, at least in part, through the significant attenuation of DNA synthesis (Androulakis et al., 2006). Olugbami et al. (2017) systematically demonstrated the potent antiproliferative effects of a hydroethanolic stem bark extract of Khaya senegalensis against HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. The extract induced a concentration- and time-dependent suppression of cell proliferation, as quantified by a significant reduction in total cell counts. Furthermore, morphometric analysis revealed a concomitant decrease in the nuclear size of viable cells, a phenomenon often associated with cell cycle arrest and the inhibition of mitotic activity. This reduction in nuclear area suggests that Khaya senegalensis stem bark impairs critical processes driving cellular replication, positioning it as a promising candidate for inhibiting the uncontrolled growth characteristic of liver cancer (Olugbami et al., 2017).

3.2 Cytotoxic Effects

Olugbami et al. (2017) comprehensively characterized the cytotoxic profile of the hydroethanolic stem bark extract of Khaya senegalensis against HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells. The extract demonstrated direct concentration- and time-dependent cytotoxicity (Fig. 1), with a CC₅₀ value of 83.92 µg/mL at 24 hours that significantly decreased upon 72-hour exposure, indicating cumulative cellular damage. Mechanistic investigations revealed that Khaya senegalensis stem bark induces a multifaceted death response, primarily initiated through mitochondrial intoxication, as evidenced by profound ATP depletion preceding loss of membrane integrity. This bioenergetic crisis was accompanied by significant oxidative stress, demonstrated by depletion of reduced glutathione (GSH) and increased oxidized glutathione (GSSG) levels. The cell death modality exhibited concentration-dependent characteristics: while activation of apoptotic pathways was observed, the predominant morphological features, particularly significant nuclear swelling, indicated a shift toward necrotic death at higher concentrations.

This mixed apoptosis-necrosis death phenotype, resulting from combined mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress, represents a potent mechanism against cancer cells that may circumvent conventional resistance pathways (Olugbami et al., 2017). Complementing the cellular findings, Olugbami et al. (2017) employed a carrot disk assay to evaluate the antitumor potential of Khaya senegalensis stem bark in planta. The extract potently inhibited crown gall tumor formation induced by Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a soil bacterium that transfers oncogenic DNA (T-DNA) into plant cells via a mechanism molecularly analogous to bacterial type IV secretion systems in mammals. The observed suppression of this genetic transformation process suggests that Khaya senegalensis stem bark contains bioactive compounds capable of interfering with fundamental oncogenic events, such as DNA transfer or integration, highlighting its potential to target conserved pathways relevant to carcinogenesis (Olugbami et al., 2017).

3.3 Inhibiting Angiogenesis and Metastasis

A tumor cannot grow or spread without creating its own blood supply (angiogenesis) (Sani et al., 2020). Pioneering work by AlQathama et al. (2020) identified Khaya senegalensis as a source of potential anti-metastatic agents (Fig. 1). The stembark decoction significantly impaired the migration of highly metastatic B16-F10 melanoma cells. This inhibitory effect was demonstrated to be concentration-independent within the tested range, remaining active at both the Maximum Non-Toxic Concentration (MNTC) and the Growth Inhibition 50 (GI₅₀) level. This finding positions K. senegalensis as a compelling candidate for further research into natural products that target the metastatic cascade (AlQathama et al., 2020).

An important contribution by Olugbami et al. (2017) utilized Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) to provide biophysical evidence of the antimetastatic potential of the hydroethanolic stem bark extract of Khaya senegalensis. Nanomechanical profiling demonstrated that treatment with Khaya senegalensis stem bark induced a 4.0-fold increase in the Young’s modulus (a measure of cell stiffness) of HepG2 cells at a concentration of 50 µg/mL. This is a critically important result, as increased cellular deformability is a well-established biophysical hallmark of metastatic cells, enabling migration and invasion through dense extracellular matrices. By significantly counteracting this pathological softness and promoting cytoskeletal rigidity, Khaya senegalensis stem bark demonstrates a compelling mechanism to potentially impede the mechanical drivers of metastasis, a property that is highly sought after in anticancer drug discovery (Olugbami et al., 2017).

3.4 Induction of Cell Cycle Arrest

Cancer is, at its core, uncontrolled division. Extracts from the plant have demonstrated a powerful ability to arrest the cell cycle. Androulakis et al. (2006) reported that Khaya senegalensis bark extract treatment disrupts cell cycle dynamics, leading to distinct arrest profiles (Fig. 1). Their results indicated a G2-phase arrest and concomitant suppression of DNA synthesis in the S-phase for HCA-7 cells. In contrast, HT-29 cells exhibited a G1-phase arrest with a strong inhibition of the S-phase following treatment (Androulakis et al., 2006).

3.5 Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant potential of Khaya senegalensis bark extract, a key component of its chemopreventive profile, was quantitatively assessed by Androulakis et al. (2006). Using a DPPH assay, the extract exhibited potent dose-dependent free radical-scavenging activity, reaching ~90% efficacy at a concentration of 4.00 μg/μl, demonstrating efficacy on par with the common synthetic antioxidant BHT. Phytochemical analysis directly linked this robust activity to a high concentration of phenolic compounds, measured at 30.71 μg GAE/mg of extract (Fig. 1), suggesting these constituents are significant contributors to the observed antioxidant effects (Androulakis et al., 2006).

3.6 Anti-Inflammatory and COX-2 Independent Mechanisms

A pivotal study by Androulakis et al. (2006) elucidated a dual mechanism of action for Khaya senegalensis bark extract, operating through both anti-inflammatory (Fig. 1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-independent pathways. The extract selectively inhibited COX-2 protein expression in a dose-dependent manner in COX-2-positive cell lines (HCA-7 and HT-29) without altering constitutive COX-1 levels. This specific inhibition subsequently led to a significant reduction (30-46%) in the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE₂), a key pro-tumorigenic inflammatory mediator (Androulakis et al., 2006)

Notably, Khaya senegalensis bark extract also demonstrated potent efficacy against the HCT-15 cell line, which is deficient in both COX-1 and COX-2, confirming that its anticancer properties extend beyond COX-2 suppression. In this COX-null model, Khaya senegalensis bark extract induced a distinct mechanistic profile, characterized by the upregulation of the tumor suppressor PPARγ and the downregulation of the cell cycle promoter Cyclin D1. This finding indicates the activation of alternative, COX-independent pathways that contribute to its overall anti-proliferative effects (Androulakis et al., 2006). This extensive traditional use has spurred considerable scientific inquiry, with research focused on validating its pharmacological activities and identifying the active chemical constituents(W.-Y. Zhang et al., 2018). Modern studies have confirmed that extracts from the stem bark possess a remarkable range of bioactivities, notably anti-inflammatory, antioxidant (Androulakis et al., 2006), antibacterial (Koné et al., 2004), and anti-plasmodial.(Androulakis et al., 2006) and antitumor effects (H. Zhang et al., 2007a; W.-Y. Zhang et al., 2018).

3.7 Induction of Apoptosis

Androulakis et al. (2006) demonstrated that Khaya senegalensis bark extract potently induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells through the activation of both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Mechanistically, treatment with Khaya senegalensis bark extract led to the downregulation of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, thereby disrupting mitochondrial integrity and promoting the release of pro-apoptotic factors (Fig. 1). This was followed by the cleavage and activation of key executioner caspases-3 and -9, as evidenced by a decrease in pro-caspase levels and a concomitant increase in their active forms. Functional validation via enzymatic assay confirmed a dose-dependent increase in caspase-3 activity of up to 97%, underscoring the central role of caspase-mediated apoptosis in Khaya senegalensis bark extract’s anti-tumor effects (Androulakis et al., 2006). Olugbami et al. (2017) provided evidence that the hydroethanolic stem bark extract of Khaya senegalensis induced programmed cell death by demonstrating a concentration-dependent activation of executioner caspases-3 and -7, key mediators of the apoptotic cascade.

This suggests the engagement of intrinsic or extrinsic apoptotic pathways. Interestingly, the activation profile was biphasic; caspase activity diminished at the highest concentrations tested. This attenuation is likely a consequence of a shift in the primary mode of cell death from apoptosis to rapid necrosis, a transition often observed with potent cytotoxic agents, where overwhelming cellular damage bypasses regulated death pathways (Olugbami et al., 2017).

3.8 Anticancer potentials of limonoids from Khaya senegalensis

The long history of ethnobotanical use of Khaya senegalensis in the treatment of cancer has made it a prime target for phytochemical investigation, driven by a compelling question: what bioactive compounds are responsible for its purported anticancer properties? The answer lies in the most significant and well-studied group of constituents, the limonoids. Approximately 45 distinct limonoids have been isolated from various parts of K. senegalensis, including the leaves, seeds, and stem bark, and are recognized as the primary bitter principles(Li et al., 2015). Limonoids are a class of highly oxidized triterpenoids known for their structural complexity(Li et al., 2015; W.-Y. Zhang et al., 2018). These compounds, which include mexicanolides and the even more complex phragmalins, are not merely abundant but exhibit a remarkable structural diversity that underpins their selective biological effects. This sophistication is exemplified by the plant’s tendency to remodel classic limonoid frameworks, such as isomerizing the typical furan ring to hydroxy- or methoxybutenolide motifs, a modification with significant implications for bioactivity(Li et al., 2015).

The biological effects of these limonoids are both potent and highly structure-dependent. For instance, a pivotal study by Zhang et al. (2007) first explored the antiproliferative potential of structurally similar analogues of limonoids, 3α,7α-dideacetylkhivorin A and 1-O-acetylkhayanolide B, from the stem bark of K. senegalensis. While 1-O-acetylkhayanolide B showed negligible effects, 3α,7α-dideacetylkhivorin demonstrated remarkable, dose-dependent cytotoxicity against breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7), cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SiHa), and colorectal adenocarcinoma (Caco-2) cancer cell lines, with IC₅₀ values in the sub-micromolar range, providing a molecular basis for the plant’s traditional use. This striking difference in activity underscores a strong structure-activity relationship, likely attributable to the presence of a 14,15β-epoxide group in compound 1, though the precise mechanism remains to be fully elucidated (Zhang et al., 2007).

Further expanding this pharmacological repertoire, modified limonoids demonstrate how specific structural alterations can enhance or diversify activity. The mexicanolide khaysenelide G, which features a methoxybutenolide group, exhibits dual cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory properties, inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and suppressing nitric oxide production in macrophages. The stark loss of activity in closely related analogs underscores the exquisite precision of SAR in this species. Thus, the bioactivity of K. senegalensis limonoids is not one of broad, nonspecific toxicity but rather of targeted efficacy, where distinct molecular architectures unlock specific and potent therapeutic mechanisms.

4.0 Conclusion and Future Direction

The systematic investigation of Khaya senegalensis reveals a compelling case for its role in the future of anticancer drug discovery. This review has delineated how the plant’s extensive traditional use against tumors and abnormal growths is strongly supported by modern pharmacological evidence. The bioactivity of K. senegalensis is not monolithic but rather a multifaceted attack on cancer hallmarks. Extracts and isolated compounds, particularly its prolific class of limonoids, demonstrate potent efficacy by inhibiting proliferation, inducing cell cycle arrest, triggering caspase-dependent apoptosis, and impairing critical metastatic processes like cell migration and deformability. Notably, its ability to operate through both COX-2-dependent and independent pathways, including the upregulation of tumor suppressors like PPARγ, suggests a versatility that could help overcome common resistance mechanisms.

The potent, structure-dependent activity of its limonoids, such as 3α,7α-dideacetylkhivorin, underscores a sophisticated structure-activity relationship that offers a blueprint for the rational design of novel therapeutics. However, the current body of information, while promising, is primarily confined to in vitro and ex vivo models. Therefore, the promising preclinical information presented herein must be followed by rigorous in vivo studies to validate efficacy, determine pharmacokinetics, and establish safety profiles in animal models. Future research should prioritize the bioassay-guided isolation of specific active limonoids, thorough mechanistic elucidation of their molecular targets, and exploration of synergistic effects within multi-component extracts. By bridging the profound wisdom of traditional medicine with cutting-edge scientific inquiry, Khaya senegalensis stands as a testament to nature’s pharmacy and a promising beacon for developing the next generation of anticancer agents.

Declaration of competing interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability: No data were used for the research described in this article.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This research received no external funding

REFERENCES

- Abdelgaleil, S. A. M., Iwagawa, T., Doe, M., & Nakatani, M. (2004). Antifungal limonoids from the fruits of Khaya senegalensis. Fitoterapia, 75(6), 566–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2004.06.001

- Aguoru, C. U., Bashayi, C. G., & Ogbonna, I. O. (2017). Phytochemical profile of stem bark extracts of Khaya senegalensis by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy, 9(3), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPP2016.0416

- AlQathama, A., Ezuruike, U. F., Mazzari, A. L. D. A., Yonbawi, A., Chieli, E., & Prieto, J. M. (2020). Effects of Selected Nigerian Medicinal Plants on the Viability, Mobility, and Multidrug-Resistant Mechanisms in Liver, Colon, and Skin Cancer Cell Lines. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.546439

- Androulakis, X. M., Muga, S. J., Chen, F., Koita, Y., Toure, B., & Wargovich, M. J. (2006). Chemopreventive effects of Khaya senegalensis bark extract on human colorectal cancer. Anticancer Research, 26(3B), 2397–2405.

- Arnold, R., & Arnold, R. (2004). Khaya senegalensis—Current use from its natural range and its potential in Sri Lanka and elsewhere in Asia. Prospects for High Value Hardwood Timber Plantations in the ’ Dry’ Tropics of Northern Australia Proceedings of a Workshop Held in Mareeba, North Queensland, Australia,19-21 October 2004, 1–9.

- Agwupuye, E. I., Agboola, A. R., Kuo, Y. C., Itam, A. H., Ezeayinka, L. U., Atangwho, I. J., … & Huang, H. S. (2025). Theobroma cacao seed extracts attenuate dyslipidemia and oxidative stress in L-NAME induced hypertension in Wistar rats. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 22(16), 4509.

- Azeez, A. A., Azeez, A. T., & Ayeyemi, B. M. (2025). From nuisance to necessity: Documenting the ethnomedicinal importance of weeds in Ondo State Nigeria. Ife Journal of Science, 27(1), 11-20.

- Arnold, R., James. (2004). (PDF) Antidiarrheal Evaluation of Aqueous and Ethanolic Stem Bark Extracts of Khaya senegalensis A. Juss (Meliaceae) in Albino Rats. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235984583_Antidiarrheal_Evaluation_of_Aqueous_and_Ethanolic_Stem_Bark_Extracts_of_Khaya_senegalensis_A_Juss_Meliaceae_in_Albino_Rats

- Asma, S. T., Acaroz, U., Imre, K., Morar, A., Shah, S. R. A., Hussain, S. Z., Arslan-Acaroz, D., Demirbas, H., Hajrulai-Musliu, Z., Istanbullugil, F. R., Soleimanzadeh, A., Morozov, D., Zhu, K., Herman, V., Ayad, A., Athanassiou, C., & Ince, S. (2022). Natural Products/Bioactive Compounds as a Source of Anticancer Drugs. Cancers, 14(24), 6203. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14246203

- Ataba, E., Katawa, G., Ritter, M., Ameyapoh, A. H., Anani, K., Amessoudji, O. M., Tchadié, P. E., Tchacondo, T., Batawila, K., Ameyapoh, Y., Hoerauf, A., Layland, L. E., & Karou, S. D. (2020). Ethnobotanical survey, anthelmintic effects and cytotoxicity of plants used for treatment of helminthiasis in the Central and Kara regions of Togo. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies, 20(1), 212. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-020-03008-0

- Birat, K., Binsuwaidan, R., Siddiqi, T. O., Mir, S. R., Alshammari, N., Adnan, M., Nazir, R., Ejaz, B., Malik, M. Q., Dewangan, R. P., Ashraf, S. A., & Panda, B. P. (2022). Report on Vincristine-Producing Endophytic Fungus Nigrospora zimmermanii from Leaves of Catharanthus roseus. Metabolites, 12(11), 1119. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo12111119

- Cao, W., Chen, H.-D., Yu, Y.-W., Li, N., & Chen, W.-Q. (2021). Changing profiles of cancer burden worldwide and in China: A secondary analysis of the global cancer statistics 2020. Chinese Medical Journal, 134(7), 783–791. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000001474

- Elisha, I. L., Makoshi, M., Makama, S., Dawurung, C., Offiah, N., Gotep, J., Oladipo, O., & Shamaki, D. (2013). Antidiarrheal Evaluation of Aqueous and Ethanolic Stem Bark Extracts of Khaya senegalensis A. Juss (Meliaceae) in Albino Rats. Pakistan Veterinary Journal, 33, 32–36.

- Fatiregun, O. A., Bakare, O., Ayeni, S., Oyerinde, A., Sowunmi, A. C., Popoola, A., Salako, O., Alabi, A., & Joseph, A. (2020). 10-Year Mortality Pattern Among Cancer Patients in Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Ikeja, Lagos. Frontiers in Oncology, 10, 573036. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.573036

- Gallego-Jara, J., Lozano-Terol, G., Sola-Martínez, R. A., Cánovas-Díaz, M., & de Diego Puente, T. (2020). A Compressive Review about Taxol®: History and Future Challenges. Molecules, 25(24), 5986. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25245986

- Gourd, K., & Collingridge, D. (2022). Cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: The time to act is now. The Lancet. Oncology, 23(6), 701–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00208-X

- Ibrahim, M. A., Koorbanally, N. A., & Islam, M. S. (2014). Antioxidative activity and inhibition of key enzymes linked to type-2 diabetes (α-glucosidase and α-amylase) by Khaya senegalensis. Acta Pharmaceutica (Zagreb, Croatia), 64(3), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.2478/acph-2014-0025

- Idu, M., Erhabor, J., Ovuakporie-Uvo, O., & Obayagbona, N. (2014). Antimicrobial qualities, phytochemistry and micro-nutritional content of Khaya senegalensis (Desr.) A. Juss seed oil. The Journal of Phytopharmacology, 3, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.31254/phyto.2014.3204

- Inngjerdingen, K., Nergård, C. S., Diallo, D., Mounkoro, P. P., & Paulsen, B. S. (2004). An ethnopharmacological survey of plants used for wound healing in Dogonland, Mali, West Africa. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 92(2), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.021

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) 2019. Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2019 <www.iucnredlist.org>. Consulted in 10 June 2014.

- Ka, A., Jo, A., Oa, O., & Oa, U. (2018). A survey of stem bark used in traditional health care practices in some popular herbal markets in Osun state, Nigeria. Journal of Medicinal Plants Studies, 6(6), 08–12.

- Kubmarawa, D., Khan, M. E., Punah, A. M., & Hassan, M. (2008). Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial efficacy of extracts from Khaya senegalensis against human pathogenic bacteria. African Journal of Biotechnology, 7(24). https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajb/article/view/59636

- Langa, A. M., Padonou, E. A., Akabassi, G. C., Akakpo, B. A., & Assogbadjo, A. E. (2024). Diversity and Structure of Khaya Senegalensis (desr.) A.Juss Habitats Along Phytogeographical Zones in Chad (Central Africa): Implications for Conservation and Sustainable Use. Journal of Environmental Geography, 17(1–4), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.14232/jengeo-2024-45530

- Li, Y., Lu, Q., Luo, J., Wang, J., Wang, X., Zhu, M., & Kong, L. (2015). Limonoids from the stem bark of Khaya senegalensis. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 63(4), 305–310. https://doi.org/10.1248/cpb.c14-00770

- Magassouba, F. B., Diallo, A., Kouyaté, M., Mara, F., Mara, O., Bangoura, O., Camara, A., Traoré, S., Diallo, A. K., Zaoro, M., Lamah, K., Diallo, S., Camara, G., Traoré, S., Kéita, A., Camara, M. K., Barry, R., Kéita, S., Oularé, K., … Baldé, A. M. (2007). Ethnobotanical survey and antibacterial activity of some plants used in Guinean traditional medicine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 114(1), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.009

- Malami, I., Jagaba, N. M., Abubakar, I. B., Muhammad, A., Alhassan, A. M., Waziri, P. M., Yakubu Yahaya, I. Z., Mshelia, H. E., & Mathias, S. N. (2020). Integration of medicinal plants into the traditional system of medicine for the treatment of cancer in Sokoto State, Nigeria. Heliyon, 6(9), e04830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04830

- Marius, Traore, T. K., & Ouedraogo. (2020). (PDF) Antioxidants activities study of different parts of extracts of Khaya senegalensis (Desr.) A. Juss. (Meliaceae). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349279427_Antioxidants_activities_study_of_different_parts_of_extracts_of_Khaya_senegalensis_Desr_A_Juss_Meliaceae

- Ngwa, W., Addai, B. W., Adewole, I., Ainsworth, V., Alaro, J., Alatise, O. I., Ali, Z., Anderson, B. O., Anorlu, R., Avery, S., Barango, P., Bih, N., Booth, C. M., Brawley, O. W., Dangou, J.-M., Denny, L., Dent, J., Elmore, S. N. C., Elzawawy, A., … Kerr, D. (2022). Cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: A Lancet Oncology Commission. The Lancet Oncology, 23(6), e251–e312. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00720-8

- Okieimen, F. E., & Eromosele, C. O. (1999). Fatty acid composition of the seed oil of Khaya senegalensis. Bioresource Technology, 69(3), 279–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0960-8524(98)00190-4

- Olatunji, T. L., Odebunmi, C. A., & Adetunji, A. E. (2021). Biological activities of limonoids in the Genus Khaya (Meliaceae): A review. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 7(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43094-021-00197-4

- Olugbami, J. O., Damoiseaux, R., France, B., Gbadegesin, M. A., Stieg, A. Z., Sharma, S., Odunola, O. A., & Gimzewski, J. K. (2017). Atomic force microscopy correlates antimetastatic potentials of HepG2 cell line with its redox/energy status: Effects of curcumin and Khaya senegalensis. Journal of Integrative Medicine, 15(3), 214–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60337-6

- Omotoyinbo, B. I., Afe, A. E., Kolapo, O. S., & Alagbe, O. V. (2019, January 22). Bioactive Constituents of Essential Oil from Khaya senegalensis (Desr.) Bark Extracts. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajcbe.20180202.13

- Orobator, E., Nnodumele, C., Tsegay, N., Onyekwelu, P., Odenigbo, A., Ugbor, M. J., … & Elechi, K. (2025). Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Plant-Based Anticancer Drug Discovery and Development. Journal of Pharma Insights and Research, 3(2), 203-210.

- Rabadeaux, C., Vallette, L., Sirdaarta, J., Davis, C., & Cock, I. (2017). An examination of the Antimicrobial and Anticancer Properties of Khaya senegalensis (Desr.) A. Juss. Bark Extracts. Pharmacognosy Journal, 9(4), 504–518. https://doi.org/10.5530/pj.2017.4.82

- Sahu, S. K., Liu, M., Wang, G., Chen, Y., Li, R., Fang, D., Sahu, D. N., Mu, W., Wei, J., Liu, J., Zhao, Y., Zhang, S., Lisby, M., Liu, X., Xu, X., Li, L., Wang, S., Liu, H., & He, C. (2023). Chromosome-scale genomes of commercially important mahoganies, Swietenia macrophylla and Khaya senegalensis. Scientific Data, 10(1), 832. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02707-w

- Sani, S., Messe, M., Fuchs, Q., Pierrevelcin, M., Laquerriere, P., Entz-Werle, N., Reita, D., Etienne-Selloum, N., Bruban, V., & Choulier, L. (2020). Biological relevance of RGD-integrin subtype-specific ligands in cancer. ChemBioChem.

- Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

- Takin, M. C., ATTINDEHOU, S., SEZAN, A., ATTAKPA, S. E., & BABA-MOUSSA, L. (2013). Bioactivity, therapeutic utility and toxicological risks of Khaya senegalensis.https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/sea-157266

- Tchacondo, T., Karou, S., Agban, A., Bako, M., Batawila, K., Bawa, M., Gbeassor, M., & de Souza, C. (2012). Medicinal Plants Use in Central Togo (Africa) with an Emphasis on the Timing. Pharmacognosy Research, 4(2), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-8490.94724

- Yuan, C.-M., Zhang, Y., Tang, G.-H., Li, S.-L., Di, Y.-T., Hou, L., Cai, J.-Y., Hua, H.-M., He, H.-P., & Hao, X.-J. (2012). Senegalensions A–C, Three Limonoids from Khaya senegalensis. Chemistry – An Asian Journal, 7(9), 2024–2027. https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.201200320

- Zhang, H., Wang, X., Chen, F., Androulakis, X. M., & Wargovich, M. J. (2007a). Anticancer activity of limonoid from Khaya senegalensis. Phytotherapy Research, 21(8), 731–734. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.2148

- Zhang, H., Wang, X., Chen, F., Androulakis, X. M., & Wargovich, M. J. (2007b). Anticancer activity of limonoid from Khaya senegalensis. Phytotherapy Research, 21(8), 731–734. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.2148

- Zhang, W.-Y., Qiu, L., Lu, Q.-P., Zhou, M.-M., Luo, J., & Li, Y. (2018). Furan fragment isomerized mexicanolide-type Limonoids from the stem barks of Khaya senegalensis. Phytochemistry Letters, 24, 110–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytol.2018.01.020